Mick Waters

Making learning Irresistible

Last weekend was my first experience of the Coventry Learning Partnership Plus conference, and unfortunately I didn't really get the full flavour of all the excellent workshops going on because my school volunteered me to run one! What I did have was the privilege of hearing Professor Mick Waters talk to us on the Friday night about making learning irresistible. He talked for 90 minutes. It barely felt like 10.

I talked to several people afterwards about what they'd taken from the speech. We were all inspired, but could we put our finger on what exactly the thrust of the talk had been? Could we hell! This blog is my attempt to try and draw some conclusions from what I heard, and summarise where Professor Waters thinks we should be heading in education, a direction I have to say from the outset that I whole-heartedly agree with.

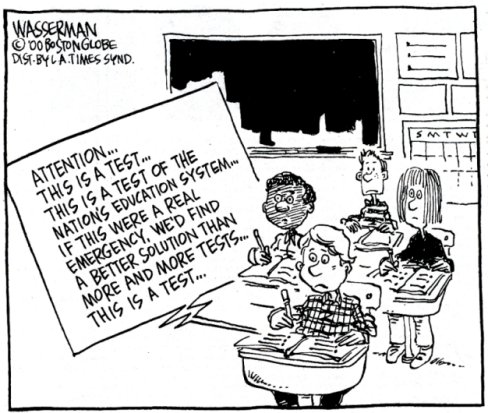

By way of personal context, there has been a lot of talk in our leadership team at school about the role of character in a child's education, about teaching more than simply content, "subjects", and even learning skills. Our current education system seems intent on reducing the really important things we teach our children to lip-service, as it is perhaps not deemed to be measurable, valuable or, dare I use the jargon du jour, "rigorous". This isn't a party political point, as I think the last government's focus on targets, attainment etc are equally blame-worthy in this respect. And nor am I saying we shouldn't be accountable for our results. I am simply arguing that our present focus on what can be measured has created an unhealthy obsession with those things over the other important areas of our educational remit, namely to help students to discover who they are, what they can do, to foster their curiosity, to nurture their talents and interests, and to get them to understand how to accomplish their goals meaningfully in a way which is as beneficial to society as it is to them. Children who care, rather than children who spend, perhaps. Though I'm told this is bad for the economy. By which of course we mean the rich folk at the top of it. Moving on...

By way of personal context, there has been a lot of talk in our leadership team at school about the role of character in a child's education, about teaching more than simply content, "subjects", and even learning skills. Our current education system seems intent on reducing the really important things we teach our children to lip-service, as it is perhaps not deemed to be measurable, valuable or, dare I use the jargon du jour, "rigorous". This isn't a party political point, as I think the last government's focus on targets, attainment etc are equally blame-worthy in this respect. And nor am I saying we shouldn't be accountable for our results. I am simply arguing that our present focus on what can be measured has created an unhealthy obsession with those things over the other important areas of our educational remit, namely to help students to discover who they are, what they can do, to foster their curiosity, to nurture their talents and interests, and to get them to understand how to accomplish their goals meaningfully in a way which is as beneficial to society as it is to them. Children who care, rather than children who spend, perhaps. Though I'm told this is bad for the economy. By which of course we mean the rich folk at the top of it. Moving on...Professor Waters' starter for the ten is the contention that, in order to prepare for and learn about the outside world, the UK for some reason corrals students behind a fence, in institutions where we actually ignore and fall behind the real world all the time. We are obsessed by the need to get on, get through the content, and miss out on the chance to make things come alive. In our efforts to have our students undertake "meaningful" activities all the time, while taking the register for example (we make them do planner checks, numeracy activities, give them tonnes of information etc), we fail to realise that the real world is always there to be tapped into.

Our focus on results has another very negative effect on students: We label them. And we label them in a way which stigmatises them deeply, despite the fact that what we are labelling is transient. One child can't do equations yet. Another has difficulties focusing at a certain time of day. Another can't get to grips with a couple of particular subjects, so we label them "Not achieving 5 A*-C grades"! Here's the thing though: If you were to grade yourself in different subjects at different times, how would you fair? On a scale of Outstanding to Unsatisfactory, how would you rate your own abilities in relation to gardening, decorating, writing, taking photographs, playing an instrument or learning a language? I imagine few of us would be excellent all-rounders, but that's not to say we don't have serious talents in one or more areas: Just look at Einstein. Bit of a failure in school by all accounts. Likewise, students are at different levels in different subjects at different times, but our need to measure things makes it easy for us to focus on the numbers and not the child in front of us. Do the numbers really tell the story? Oddly enough I was listening to a Radio Four business programme the other day where several chief execs were agreeing on this very point, and saying that the data they got on their desks every day was a deeply inferior diagnostic tool compared to direct contact with their people on the ground floor and their customers. A lesson for us all perhaps...

Our focus on results has another very negative effect on students: We label them. And we label them in a way which stigmatises them deeply, despite the fact that what we are labelling is transient. One child can't do equations yet. Another has difficulties focusing at a certain time of day. Another can't get to grips with a couple of particular subjects, so we label them "Not achieving 5 A*-C grades"! Here's the thing though: If you were to grade yourself in different subjects at different times, how would you fair? On a scale of Outstanding to Unsatisfactory, how would you rate your own abilities in relation to gardening, decorating, writing, taking photographs, playing an instrument or learning a language? I imagine few of us would be excellent all-rounders, but that's not to say we don't have serious talents in one or more areas: Just look at Einstein. Bit of a failure in school by all accounts. Likewise, students are at different levels in different subjects at different times, but our need to measure things makes it easy for us to focus on the numbers and not the child in front of us. Do the numbers really tell the story? Oddly enough I was listening to a Radio Four business programme the other day where several chief execs were agreeing on this very point, and saying that the data they got on their desks every day was a deeply inferior diagnostic tool compared to direct contact with their people on the ground floor and their customers. A lesson for us all perhaps...So back to the students: Most of us start out positively in school, but even with the best of intentions, because we can't invest sufficient time to master a skill to the outcome level we want, we end up as "disillusioned triers" who give up on our ability to learn it. Waters does a great experiment with kids: He asks them how they would rate themselves in all of their school subjects. Apparently you never get more than 40% say they're any good at something. But if you ask them about how good they will be at driving and learning to drive, and whether they'll be any good as drivers, they respond overwhelmingly positively. About something they've never tried before. Is it the learning experience which puts us down, or the labeling which occurs along the way?

Similarly we could ask as professionals whether a teacher whose lesson is described as "satisfactory" is actually a satisfactory teacher? Or is this just a label? A snapshot. Under pressure too. Like a terminal exam even. Strikes me as a bit unfair to judge us this way on an annual basis, never mind judging a whole school every four years using that method. But boy do we bust a gut to get the "Outstanding" label! Professor Waters' conclusion was that the Outstanding teacher teaches good lessons consistently, but more than that: He or she also looks after the lonely child in the corridor. Is the latter any less important that the former? Are the teacher who have left a life-long impression on your lives the ones who taught tight formulaic "Outstanding" lessons every day? Or the ones who cared? Who took the time to listen to you? Who took a genuine interest in you as a person?

Many Outstanding schools are outstanding because they follow "the trudge", and they do it well, and have hit the right formula. The relentless focus on "5 A*-C grades", "RAISEOnline", CVA, the systematic monitoring, the countless interventions: All of these serve to get as many students as possible over that finish line which the data says they should cross, based on mathematical probabilities and algorithms we shouldn't question because they're far too complex for us to understand. And then they suspend the timetable for a day occasionally so that they can do a whole-school activity which will provide the rounding out of their characters (!) which society also requires. Are we really delivering that? Not according to Mick Waters', industry, the government, the parents or the Daily Mail!

Many Outstanding schools are outstanding because they follow "the trudge", and they do it well, and have hit the right formula. The relentless focus on "5 A*-C grades", "RAISEOnline", CVA, the systematic monitoring, the countless interventions: All of these serve to get as many students as possible over that finish line which the data says they should cross, based on mathematical probabilities and algorithms we shouldn't question because they're far too complex for us to understand. And then they suspend the timetable for a day occasionally so that they can do a whole-school activity which will provide the rounding out of their characters (!) which society also requires. Are we really delivering that? Not according to Mick Waters', industry, the government, the parents or the Daily Mail!A futures learning outlook

What we really need is to focus on what we hope for our students. The government is more focused on the core of knowledge, but we should be producing rounded human beings, and enthusiastic, curious learners. An outstanding teacher's role is to raise the spirits and self-esteem of their students, and to raise their gaze so that they look up at the world around them and see themselves as part of it. Our role is to help them find out who they are, and how they can make a positive difference to the world, and find a sense of their own happiness within the roles they choose for themselves. Our curriculum should be based on the big questions, with students clear about how the small matters fit into the bigger picture. It should prepare them to tackle big questions, and connect to the real world every lesson. Every child should be able to see the relevance of lessons for life in the big wide world as it is today. But I would suggest that this is just one aim. The second, and more important one as far as I am concerned, is this: If we start by showing students how their learning connects to the real world as it is, we should also be fostering the kind of curiosity and thinking which will help them shape the society that we could have. Because demonstrating to students how they could fit into modern society means we implicitly accept everything about that society, including its values and priorities. And I for one think that this demonstrates a real paucity of ambition. I would hope that our children can do a better job of society than we have. But it's unlikely to happen if we persist in telling them that what we have now is the only way it can be done.

The best summary of this perspective I've ever seen was written by a man named Kahlil Gibran, in a brilliant book full of wisdom call The Prophet. Given the daily vacillations in education policy and debate in this country, these thoughts help to anchor me as a teacher and a parent.

Your children are not your children.

They are the sons and daughters of Life's longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you, yet they belong not to you.

You may give them your love but not your thoughts.

For they have their own thoughts.

You may house their bodies but not their souls,

For their souls dwell in the house of tomorrow, which you cannot visit, not even in your dreams.

You may strive to be like them, but seek not to make them like you.

For life goes not backward nor tarries with yesterday.

You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth.

The archer sees the mark upon the path of the infinite,

And He bends you with His might that His arrows may go swift and far.

Let your bending in the archer's hand be for gladness;

For even as he loves the arrow that flies, so He loves also the bow that is stable.

Acceptance of the status quo and trying to incrementally tweak it tends to be what kills large companies. Large role cultures have little capacity for change. Microsoft and Nokia are recent examples but Apple is now having similar problems. IBM lost 40 billion in the early 90s and was only saved by reinventing itself as a service company. Since it costs £6000 a year to educate a child, 15 generate £90,000 a year. If I was paid 90 k a year for a class of 15 I could fit them in a room at home install some IT and I think teach them effectively to at least GCSE in any subject. https://theingots.org/community/How_to_pay_teachers_90k_a_year

ReplyDeleteWe never really think about that level of change or the incremental costs of adding often well intentioned layer after layer of "support". Perhaps its not surprising that we have a lot of difficulty producing independent learners when the culture of dependency is so firmly ingrained in the organisational structures.